Media play an important role in shaping public perception of foreign news (Aalberg et al., 2013; Biltereyst & Desmet, 2010; Peterson, 1979; Sreberny-Mohammadi et al., 1985). At the same time, the adaptation of distant events to the values, social stereotypes, needs, problems, and cultural characteristics of mass media consumers has key importance (Bouman et al., 2015; Galtung & Ruge, 1965; Joye, 2010a; J. Kim & Eom, 2019).

Previous studies have thoroughly examined how media around the world integrate foreign news into national contexts (Barker, 2012; Boyd-Barrett & Rantanen, 1998; Gade & Ferman, 2011; Hepp & Couldry, 2009). They have clearly shown that the success of news coverage depends on how accurately the information messages meet the needs of the target audience (A. A. Cohen, 2002; Haddon, 2016; F. L. Lee et al., 2011).

The same applies to military reports. Like any other news, reports on distant conflicts must also be sufficiently adapted to meet the needs of their consumers (Harris & Williams, 2018; Neumann & Fahmy, 2012; Taradai, 2014; X. Zhang & Luther, 2020). For example, the U.S. media made the distant civil war in Syria (since 2011) more relevant to Americans by emphasizing the national security threats coming from the Middle East (Byman & Moller, 2016; Krieg, 2016). During the Iraq War (2003), British journalists chose a different information strategy: they focused mainly on the moral justification of their country’s participation in the military campaign (Lewis, 2006; Ravi, 2005).

At the same time, little attention has been paid to how the process of adapting foreign news unfolds in a multilingual media landscape. Contemporary studies have not thoroughly examined the set of strategies through which media within a single country present foreign news to different linguistic groups. Therefore, a gap in research on the forms and methods of presenting foreign news is noticeable in the sphere of covering important armed conflicts: there is a lack of thorough studies on how media in multicultural societies adapt and interpret news on them for different social groups.

Israel appears to be a suitable location for conducting research in this field. This is an internally diverse country with a distinctly multicultural and multilingual society, where people speak Hebrew, Russian, Arabic, English, and other languages.

Taking this fact into consideration, we will examine how the Israeli press produces and adapts news about the ongoing wars between Russia and Ukraine (since 2022) and Israel with Hamas (since 2023) in a way that makes their messages appealing to the various linguistic and cultural communities in Israel. The study of information strategies that allow Israeli media to make armed conflicts captivating for their diverse audiences will also help explain broader patterns in the cross-cultural adaptation of media narratives.

Considering the above, the aim of this study is to conduct a cross-linguistic content analysis to identify and compare journalistic methods and practices used by various Israeli media in the process of news formation for different cultural and linguistic communities. This analysis will show how media presentations differ depending on the language, as well as how these differences affect the coverage of external and internal armed conflicts. By comparing these approaches, we can better understand how media messages about dangerous and threatening phenomena are created and disseminated in a heterogeneous and complexly organized society.

The results of the study will provide valuable insights for scholars in the field of mass media and communication studies. They will also be practically useful for journalists striving to overcome the challenges of covering international and local conflicts in a diverse or divided audience.

To achieve the a content analysis of Israeli press materials will be conducted, focusing on the coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian war (since February 24, 2022) and Israel’s conflict with Hamas (since October 7, 2023). We will proceed from the assumption that media representation plays a key role in shaping public opinion and constructing media frames — both on a national scale and for specific social groups (B. C. Cohen, 2015; Hall, 1980, 1997). Therefore, the study will aim to identify and compare the journalistic methods and practices used by various Israeli media when forming news messages for different social, cultural, and linguistic groups.

We expect that this study will allow us to:

- identify, describe, and analyze the differences between specific journalistic practices in covering internal and foreign armed conflicts for different audiences within one country;

- understand how linguistic and cultural differences affect methods of news domestication;

- propose effective mechanisms for classifying, analyzing, and comparing elements of media discourse that have undergone domestication;

- provide practical recommendations to journalists to enhance the effectiveness of covering international and local armed conflicts in a multicultural society.

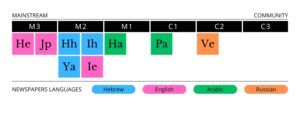

As the object of study, we will take nine Israeli mainstream and community newspapers in four languages of the largest socio-cultural communities in Israel (Hebrew, Russian, English, and Arabic). Preference will be given to print publications that have their own websites — that is, those media that combine the advantages of traditional quality press, shaping public opinion, and modern information technologies that allow for prompt and wide dissemination of information. They are:

- Haaretz (Hebrew, English, Arabic)

- The Jerusalem Post (English)

- Israel Hayom (Hebrew, English)

- Yedioth Ahronoth (Hebrew)

- Panet (Arabic)

- Vesti (Russian)

Therefore, taking into account that the typology of modern media is obviously not dichotomous but gradual, and the fact that the features of news domestication that interest us depend more on the type of target audience than directly on the type of media, we propose to conventionally place the nine Israeli newspapers we have selected for analysis on our own scale of the typology of Israeli newspapers «mainstream — community» as follows.

| MAINSTREAM NEWSPAPER TYPES

M3 — Newspapers with a strong mainstream orientation, targeting both national and international audiences. M2 — National newspapers with a significant analytical focus, covering key political and social topics. M1 — Newspapers that cover national topics with less emphasis on analytical depth. |

COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER TYPES

C1 — Community-oriented newspapers that cover important national events. C2 — Newspapers that are more focused on the interests of specific groups (communities) and less on national coverage. C3 — Exclusively local newspapers, reflecting issues just within small communities. |

|

Haaretz — [He] A globally oriented newspaper for an international audience. Focuses on Israeli and world events. A classic example of a mainstream newspaper. |

Haaretz — [Hh] Hebrew, M2 A national newspaper with an analytical approach, focusing on Israel’s political, cultural and social agenda. Covers both national and global topics. |

Haaretz — [Ha] Arabic, M1 Targets Arabic-speaking audiences, covering national topics with local elements. However, its analytical content retains broader audience appeal. |

| The Jerusalem Post — [Jp] English, M3 A fully mainstream publication focusing on global and national topics. It caters to English-speaking readers and prioritizes an international audience. |

Israel Hayom — [Ih] Hebrew, M2 A national newspaper focusing on political and social issues. Reflects a right-wing perspective, making it a prominent example of popular mainstream media. |

Israel Hayom — [Ie] English, M2 Like the Hebrew version but adapted for English-speaking audiences. Its content maintains a national focus with |

| Yedioth Ahronoth — [Ya] Hebrew, M2 A major national newspaper with a broad audience. It covers political, social, and cultural topics, combining popular and analytical content. |

Panet — [Pa] Arabic, C1 Targets Arabic-speaking communities in Israel and abroad. While it focuses on local events, it also includes some national topics, placing it in the C1 range. |

Vesti — [Ve] Focuses on the Russian-speaking community |

The choice of the above publications is primarily due to their widest audience coverage within the corresponding cultural-linguistic groups, as well as their most complete reflection of the diversity of the Israeli media landscape.

For the analysis, we will select at least ten informational-analytical articles, news notes, and journalistic materials of other genres on different topics about each of the wars under consideration from each newspaper. The analysis will cover a period of one year from the start of each war: for military actions in Ukraine — starting from February 24, 2022; for the IDF operation against Hamas — after the events of October 7, 2023. This time interval will allow us to focus on the initial period — the most significant for the formation of media frames of both conflicts — and to trace the evolution of key media approaches to covering each of them.

In our study, we will use both qualitative (content analysis to identify the journalistic techniques used, stylistic features, methods of domestication, examples of framing, priming, etc.) and quantitative (counting the frequency of mentions of certain topics, frames, message tonality, and other measurable characteristics in selected articles) methods. The work will be structured in several stages as follows.

♦1. Using classical content analysis methods (Krippendorf, 2013), we will review Israeli press materials, select and categorize articles to form a corpus of texts for study.

♦2. Using the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) method [1] (Jelodar et al., 2019), we will analyze the obtained corpus of texts (selected media materials) to identify its largest and most notable thematic categories: events, phenomena, characters, etc.

♦3. Based on the theoretical concept of framing, we will determine for each thematic category identified in the second stage its dominant frames (for example: victim, aggressor, war crime, suffering of civilians, etc.) and classify them.

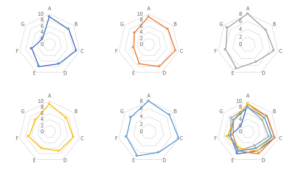

♦4. Having a list of obtained frames, we will analyze each material selected in the first stage of the Israeli press and assess all its constituent frames on a 10-point scale corresponding to the theme of the analyzed material according to the following seven criteria:

A) Frame relevance — how much the frame is related to the main theme of the text; B) Depth of disclosure — how deeply the frame is discussed in the material; C) Emotional load — how much the frame appeals to the readers’ emotions; D) Role in the text — how much the frame structures the overall narrative of the material; E) Objectivity and argumentation — how objectively the frame is presented and supported by arguments; F) Frequency of mention — how many times the frame explicitly or implicitly appears in the text; G) Ease of interpretation — how much the frame requires deep analysis or effort from the reader to understand.

♦5. We will present the results of analyzing each frame in each specific material in the form of a petal or radial diagram.

For example, in the article “How can the US use the Gaza war to expand the Abraham Accords?” (by Boaz Golany & Jacob Nagel, The Jerusalem Post, December 15, 2023, see the text of the article in Appendix №1), we can identify five main frames and assess them according to the seven abovementioned criteria.

| Frames | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| I. Normalization under threat (escalation in Gaza and Iran’s support for Hamas as key obstacles to peace in the region). | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 3 |

| II. The US as mediator and guarantor of peace (the role of the US in protecting Israel and the negotiation process). | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| III. Historical parallels (comparing proposed strategies with the Marshall Plan and the creation of NATO after WWII). | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| IV. The threat of Iran (positioning Iran as the main force seeking to disrupt the normalization process in the region). | 9 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| V. US international leadership (a call to strengthen stability and regional cooperation). | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

Based on the assessments of these frames, we can construct corresponding diagrams for each of them. In doing so, we expect that for more domesticated topics and news discourses, the average indicator of their constituent frames will tend toward a higher side (i.e., toward 10), and for less domesticated topics — toward a lower side (i.e., toward 1). When analyzing and comparing diagrams for greater clarity, we can overlay them on each other.

♦6. The availability of numerical and visualized graphic data for each frame will provide us with a convenient tool for comparing and analyzing the level of its domestication in the Israeli media landscape using Pearson’s correlation method [2] (Pearson, 1895) — one of the most convenient tools for assessing the degree of similarity of different data sets when analyzing media messages (Z. Zhang et al., 2018).

♦7. All the above will allow us to compare news domestication strategies between different media at three levels: a) the degree of coincidence of general topics; b) the degree of coincidence of the frames constituting these topics; c) the level of correlation of the frames themselves.

Based on these indicators, we propose calculating for each media outlet the so-called Domestication Convergence Index (DCI) — an indicator of the degree to which the agendas of different media oriented toward different audiences converge or diverge. Introducing this concept into scientific circulation will allow, based on the similarity or dissimilarity of domestication strategies in media oriented toward different cultural and linguistic audiences, to:

- determine how close the agenda of a particular print publication (and, consequently, the perception of its audience) is to the national one;

- measure the degree of social and cultural solidarity of society as a whole based on the dispersion of DCI indicators.

Among the limitations of the study, besides the natural limitation of the sample by time and the number of analyzed articles, there may be possible limitations in accessing full archives of some publications, as well as linguistic nuances associated with the need to translate all analyzed content into a single common language (English) for analysis, which can also affect content interpretation.

[1] A statistical topic modeling method that allows analyzing large text corpora, identifying their thematic patterns, and distributing data into corresponding topics based on a probabilistic approach.

[2] Pearson’s correlation measures the dependence between two indicators using a coefficient ranging from –1 (perfect inverse relationship) to +1 (perfect direct relationship).

References

- Aalberg, T., Papathanassopoulos, S., Soroka, S., Curran, J., Hayashi, K., Iyengar, S., & Tiffen, R. (2013). International TV news, foreign affairs interest and public knowledge: A comparative study of foreign news coverage and public opinion in 11 countries. Journalism Studies, 14(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2012.712674

- Biltereyst, D., & Desmet, L. (2010). One day of foreign and international news. In J. Gripsrud, L. Weibull, & Media (Eds.), Markets and Public Spheres (pp. 61-81). Intellect Books.

- Peterson, S. (1979). Foreign news gatekeepers and criteria of newsworthiness. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 56(1), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769907905600112

- Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. (1965). The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 64–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336500200104

- Joye, S. (2010a). News discourses on distant suffering: A critical discourse analysis of the 2003 SARS outbreak. Discourse & Society, 21(5), 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926510383196

- Kim, J., & Eom, K. (2019). Cross-cultural media effects research. In Media Effects (pp. 419–434). Routledge.

- Harris, J., & Williams, K. (2018). Reporting war and conflict. Routledge.

- Neumann, R., & Fahmy, S. (2012). Analyzing the spell of war: A war-peace framing analysis of the 2009 visual coverage of the Sri Lankan civil war in western newswires. Mass Communication and Society, 15(2), 169–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.571258

- Zhang, X., & Luther, C. A. (2020). Transnational news media coverage of distant suffering in the Syrian civil war: An analysis of CNN, Al-Jazeera English and Sputnik online news. Media, War & Conflict, 13(4), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635219900772

- McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1086/267990

- McCombs, M., Llamas, J. P., Lopez-Escobar, E., & Rey, F. (1997). Candidate images in Spanish elections: Second-level agenda-setting effects. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 74(4), 703–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909707400406

- McCombs, M., Lopez-Escobar, E., & Llamas, J. P. (2000). Setting the agenda of attributes in the 1996 Spanish general election. Journal of Communication, 50(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02870.x

- Sheafer, T., & Weimann, G. (2005). Agenda building, agenda setting, priming, individual voting intentions, and the aggregate results: An analysis of four Israeli elections. Journal of Communication, 55(2), 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02697.x

- Moy, P., Tewksbury, D., & Rinke, E. M. (2016). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy (pp. 1-13). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118766804.wbiect101

Appendix №1

How can the US use the Gaza war to expand the Abraham Accords?

Newspaper article

Authors: Boaz Golany, Jacob Nagel

Date: December 15, 2023

Source: The Jerusalem Post

Link: https://www.jpost.com/opinion/article-778098

Intelligence reports show that Hamas’s assault on Israel on October 7 was prepared over several years, with active support and guidance from Iran. The timing of the attack was motivated, to some extent, by the rapid advances in the US-led normalization process between Israel and Saudi Arabia in the weeks preceding the attack. Such a normalization could undermine the goals of both Hamas and the Iranian regime, who realized that a normalization pact would stymie their efforts to delegitimize and ultimately destroy Israel. For now, it seems their plot has partially succeeded; the normalization process came to a screeching halt and there are growing signs of tension and irritation among the Arab signatories of the Abraham Accords (the UAE, Bahrain, and Morocco) that may lead to the collapse of these agreements or their deterioration to the “cold peace” that describes relations between Israel and two of its other peace partners – Egypt and Jordan.

While the war in Gaza rages on, it is not too early for the Biden administration to consider how can it best respond to efforts aimed to derail one of its most ambitious strategic moves – expanding the circle of Arab nations that want regional peace. The US accomplished this initially by standing firmly by Israel, providing it with much needed military and financial aid, and defending it in the UN and other international bodies. This did not go unnoticed by America’s Arab allies.

But will this be enough to revive the normalization effort? Probably not. There are other possible moves similar to those taken by the US soon after WWII. This would include launching a Marshall plan equivalent to address the civilian needs of Gaza, similar to the US assistance granted to western Europe, which was largely ruined by that time. This could also include creating a Middle East NATO equivalent to address the security threat posed by Iran, similar to the way a multilateral organization was created to counter the USSR after WWII.